10Dogs Have Built-In Paw Warmers

Evolution has equipped canines with built-in paw warmers, or snow booties, that function like seat warmers in luxury automobiles. This gives dogs the remarkable ability to stave off frozen feet even when exposed to frosty or icy surfaces. A dog’s bare paws are exposed to the elements and have a high ratio of surface area to volume, which should promote heat loss. But a tightly bunched network of blood vessels keeps doggy feet at cozy temperatures in just about any terrain. The veins and arteries are in such close proximity to each other that heat from the warm blood traveling to the paws is quickly transferred to the colder blood leaving the paws, keeping the extremities balmy. In scientific terms, this is known as a countercurrent exchange system. The same mechanism is present in penguin feet and wings, dolphin fins, and the paws of arctic foxes. Its unexpected discovery in canines suggests that dog domestication may have begun in colder climates. Further insulation comes from freeze-resistant fatty reserves located within the pads, although excessive breeding has diminished this in some dog types.

9The Jurassic Period Was A Mammalian Hot Pot

Thanks to a particular line of films, we’ve come to know the Jurassic period as a dinosaurian heyday. For a while, it did appear that the only mammals present during the Mesozoic era (which includes the Jurassic period) were grubby little insectivores, active only at night as the reptilian overlords dozed. Now, an Oxford-led skeletal and dental analysis of Mesozoic mammals has revealed that this era, especially the Jurassic portion, was a time of unheralded mammalian proliferation. New versions of old animals quickly arose, filling vacant evolutionary niches with their newly gained propensities to glide, dig, and swim. The mid-Jurassic period (200–145 million years ago) witnessed mammals evolving at a rate 10 times faster than the late Jurassic, when the evolutionary ruckus finally settled. The unexpected boom led to rapidly changing body shapes and sizes as well as unprecedented dental diversity. The therian lineages that gave birth to placentals and marsupials underwent the greatest adaptive changes, growing 13 times faster than normal. As reptilians still reigned supreme, our fuzzy ancestors gained an evolutionary foothold they’d not soon relinquish.

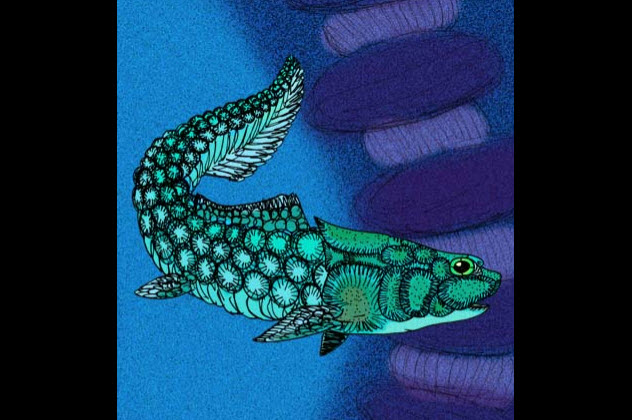

8Enamel Was For Fish

Enamel, the biological cement that caps your teeth so you can enjoy apples and peanut brittle, has a long evolutionary history. Long before it migrated into mouths, enamel served as fish armor. According to the fossilized Romundina stellina that’s 400 million years old, some of the earliest chompers were nothing more than a bumpy plate. R. stellina are among the oldest jawed vertebrates and, therefore, dental forebears to a wide variety of animals. These armor-plated fish developed a bite plate that wasn’t quite the same as teeth. Instead, it was one large toothy prominence around which smaller bumps gradually formed. However, just like the teeth of today, they were composed of a creamy dentin core surrounded by a crunchy enamel coating. Psarolepis romeri—an even older, smaller specimen adorably known as a minipredator—had dentin teeth without the protective enamel coating. It did possess this wonder material but in its scales. Some argue that similar, fully fledged scales in other creatures eventually drifted toward the mouth through assorted mutations to become modern teeth. It’s also possible that structures already present in the mouth switched function along the way and started pumping out enamel.

7Bowhead Whales Have Evolved An Auxiliary Mouth-Penis

Bowhead whales are the longest-lived of all mammals and sport the animal kingdom’s largest mouths. Yet the most striking anatomical feature of these gentle giants is a lamppost-sized organ tucked away in their meaty jaws. Despite its prodigious dimensions, the 4-meter (12 ft) corpus cavernosum maxillaris (CCM) was just discovered in the 1990s when researchers from Virginia’s Hampden-Sydney College dissected seven bowhead whales that had been previously slain by Alaskan Inupiat hunters in a government-sanctioned hunt. Hacking through the whales’ fleshy skulls, researchers spotted a rodlike appendage poking out from a lump of jaw meat. Warmer than the surrounding tissue, the mysterious structure was full of blood and thoroughly innervated. Furthermore, it was composed of a spongy tissue that hardens significantly when engorged with blood. Yup, it’s a penis all right. Though undoubtedly penile in structure and partially in function, it is not, to our knowledge, used as a sexual implement. Instead, the organ probably serves to dissipate excess body heat. To brave the icy depths, whales have become dangerously insulated, so much so that they risk overheating while engaged in strenuous activity. The warmer, highly vascular CCM supposedly combats this potentially lethal inconvenience. It’s also possible that the organ detects plankton and other small aquatic organisms as water filters through a bowhead’s cavernous mouth.

6Warm-Bloodedness

With an internal heat source, we warm-bloods enjoy a much more active lifestyle than the less fortunate creatures who rely upon the Sun. Yet endothermy did not originate with the small, furry beings that skittered about dinosaur feet at the dawn of the mammalian timeline. Researchers Christen Don Shelton and Martin Sander have traced warm-bloodedness back at least 300 million years to a monstrous dog-lizard named Ophiacodon. Of course, these animals were neither dog nor lizard. Instead, they were synapsids, creatures like the sail-backed Dimetrodon with both mammalian and reptilian traits. One of the many perks afforded to warm-bloods is an accelerated growth rate, which produces distinct bone patterns in mammals and birds. Researchers found this telltale fibrolamellar bone in Ophiacodon skeletons as well, suggesting at least a partial warm-bloodedness. Since Ophiacodons aren’t directly beneath us on the ancestral timeline, it appears that this useful evolutionary feature developed in parallel across separate biological branches.

5Penguins Can’t Taste Fish Anymore

In a cruel twist of adaptation that occurred sometime around 20 million years ago, penguins seem to have lost the ability to savor fish, their favorite snack. They still chow down on seafood, but it might as well be iceberg lettuce. The taste receptors that perceive umami, the full-bodied, meaty taste inherent to fish and other tasty animals, are no longer coded in the penguin genome. According to a genetic analysis from the University of Michigan, researchers hypothesize that living in a frigid biome has degraded the ability of penguins to enjoy a full range of flavors, based on the fact that taste receptors function poorly at low temperatures. Therefore, the nearly useless receptors faded from penguins’ mouths over time. Adding insult to injury, the taste receptors for sweet and bitter have apparently been rendered nonfunctional as well. We’re not even sure if these poor animals can perceive sour and salty sensations. In penguins, the structure for savoring salty flavors is also essential to kidney function. So it may not work for their sense of taste, possibly leaving penguins unable to perceive any flavors at all.

4Flies Are Nature’s Military Jets

Arguably nature’s most annoying invention, flies have tiny brains and face overwhelming cognitive deficiencies yet boast evasive capabilities that rival military aircraft. Nearly impossible to swat, science has found that flies analyze incoming threats and formulate a contingency plan within 100 milliseconds. Via high-speed, high-resolution imaging, researchers were able to see how fruit flies so annoyingly avoid death. Evolution has managed to pack an impressively complex avoidance system into a small insect brain as well as into its three pairs of legs. Long before your hand ever comes down, the fly’s nervous system has already integrated several tasks. Its 360-degree visual system has recorded your approaching haymaker, consulted with positioning sensors in the legs to achieve the perfect take-off, and planned an escape route while your hand was still gaining speed. To sidestep the problem, researchers suggest a Zen-like battle of wits between creature and man: Aim not for the fly, but be the fly and aim for where it will be.

3Two- And Three-Toed Sloths Are Not Really Related

Sloths of the two- and three-toed varieties are so strikingly similar that even scientists were shocked to find the resemblances were purely coincidental. A great example of convergent evolution, the shiftless sloths are only distantly related. Both are xenarthrans, sharing a presumable ancestry with land-dwelling, prominently clawed animals like anteaters and armadillos. In lieu of toppling anthills, however, antediluvian sloths used their fearsome claws as climbing spikes, populating the treetops and settling into a novel evolutionary niche as lazy, arboreal mammals. The massive, terrestrial sloths of past eons bear little semblance to their modern descendants, except for a complement of scythe-like claws. For example, modern sloths of the two-toed variety are most closely related to the extinct Megalonyx—a bearish, dopey-faced animal with a 3-meter (10 ft) body span and an occasional hankering for meat. Three-toed sloths, on the other hand, appear to be miniaturized versions of the Megatherium, an unbelievably girthy ground sloth that topped 6 meters (20 ft) in length. Luckily, these large bodies developed as a means to reach out-of-the-way vegetation because carnivorous sloths dropping from the canopy is a terrifying thought.

2Water Bears Have Borrowed A Good Portion Of Their Genome

We’ve previously mentioned that tardigrades—or in cuter terms, water bears—are amazingly indestructible creatures unaffected by ungodly temperatures, impossible pressures, and even the vacuum of space. Now for the first time, researchers have laid bare the tardigrade genome and uncovered the most foreign DNA of any living thing. Water bears are as close as we’ve come to discovering alien life. This unusual, extremely varied blueprint is the result of countless horizontal gene transfers. Generally, we think of genetic information being passed “down” through successive generations via procreation, a process called vertical gene transfer. Horizontal gene transfer is the sharing of code between organisms through nonsexual means, such as ingesting plasmids. Normally, a sturdy nuclear wall protects a creature’s precious DNA from outside meddling. However, the tardigrade’s ability to survive extreme desiccation has apparently allowed frequent intrusion into its genetic material. As the tardigrade loses water, its nuclear membranes shrivel, become brittle, and shear away, offering access to the gooey DNA within. Random bits of foreign code are swept inside, merging with their unassuming host.

1Snakes Came From Below

Almost everyone hates snakes, and until recently, it was assumed that their repulsive, slithering physiques developed many millions of years ago in some far-off, sea-dwelling ancestors. However, others argue that the agile, limbless bodies arose as an adaptation to underground living, much like the vermicular monstrosities from the Tremors franchise. Recently, an anatomical study by paleontologists Hongyu Yi and Mark Norell seems to have resigned ancestral snakes to the subterranean domain of moles and earthworms. The secret lies in the shape of the inner ear, from which researchers can ascertain a snake’s preferred biome. Burrowing animals have inflated inner ear structures that allow detection of low-frequency rumblings made by creatures scurrying through soil. An X-ray analysis of 44 fossilized and extant reptiles found the telltale inner ear balloon well represented, suggesting a belowground heritage. This most recent study confirms earlier work by John J. Wiens at Stony Brook University, which pried deep into the reptilian genome to discover the progenitors of most modern snakes: blind, ground-dwelling proto-snakes called scolecophidians.